Camille Pissarro

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Pissarro" redirects here. For other uses, see Pissarro (disambiguation).

| Camille Pissarro | |

|---|---|

Circa 1900 |

|

| Birth name | Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro |

| Born | 10 July 1830 Charlotte Amalie, Danish West Indies (US Virgin Islands) |

| Died | 13 November 1903 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Danish-French |

| Field | Painting |

| Movement | Impressionism Post-Impressionism |

| Influenced by | Eugène Delacroix, Édouard Manet, Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny |

| Influenced | Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Lucien Pissarro |

In 1873 he helped establish a collective society of fifteen aspiring artists, becoming the “pivotal” figure in holding the group together and encouraging the other members. Art historian John Rewald called Pissarro the “dean of the Impressionist painters", not only because he was the oldest of the group, but also "by virtue of his wisdom and his balanced, kind, and warmhearted personality”.[1] Cézanne said "he was a father for me. A man to consult and a little like the good Lord," and he was also one of Gauguin's masters. Renoir referred to his work as “revolutionary”, through his artistic portrayals of the "common man", as Pissarro insisted on painting individuals in natural settings without "artifice or grandeur".

Pissarro is the only artist to have shown his work at all eight Paris Impressionist exhibitions, from 1874 to 1886. As a stylistic forerunner of Impressionism, he is today considered a "father figure not only to the Impressionists" but to all four of the major Post-Impressionists, including Georges Seurat, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.[2]

Contents |

Early years

Camille Pissarro was born on July 10, 1830 on the island of St. Thomas to Frederick and Rachel Pissarro.[3][4] His father, who was of Portuguese Jewish descent, held French nationality and his mother was native Creole.[2] His father was a merchant who came to the island from France to deal with the business affairs of a deceased uncle, and married his widow. The marriage, however, caused a stir within St. Thomas’ small Jewish community, either because Rachel was outside the faith or because she was previously married to Frederick's uncle, and in subsequent years his four children were forced to attend the all-black primary school.[5] Upon his death, his will specified that his estate be split equally between the synagogue and St. Thomas’ Protestant church.[6]When Camille was twelve his father sent him to boarding school in France. He studied at the Savary Academy in Passy near Paris. While a young student, he developed an early appreciation of the French art masters. Monsieur Savary himself gave him a strong grounding in drawing and painting and suggested he draw from nature when he returned to St. Thomas, which he did when he was seventeen. However, his father preferred he work in his business, giving him a job working as a cargo clerk. He took every opportunity during those next five years at the job to practice drawing during breaks and after work.[7]

When he turned twenty-one, Danish artist Fritz Melbye, then living on St. Thomas, inspired Pissarro to take on painting as a full-time profession, becoming his teacher and friend. Pissarro then chose to leave his family and job and live in Venezuela, where he and Melbye spent the next two years working as artists in Caracas. He drew everything he could, including landscapes, village scenes, and numerous sketches, enough to fill up multiple sketchbooks. In 1855 he moved back to Paris where he began working as assistant to Anton Melbye, Fritz Melbye's brother.[8][9]

Life in France

In Paris he worked as assistant to Danish painter Anton Melbye. He also studied paintings by other artists whose style impressed him: Courbet, Charles-François Daubigny, Jean-François Millet, and Corot. He also enrolled in various classes taught by masters, at schools such as École des Beaux-Arts and Académie Suisse. But Pissarro eventually found their teaching methods “stifling,” states art historian John Rewald. This prompted him to search for alternative instruction, which he requested and received from Corot.[1]:11Paris Salon and Corot's influence

His initial paintings were in accord with the standards at the time in order to be displayed at the Paris Salon, the official body whose academic traditions dictated the kind of art that was acceptable. The Salon’s annual exhibition was essentially the only marketplace for young artists to gain exposure. As a result, Pissarro worked in the traditional and prescribed manner in order to satisfy the tastes of its official committee.[7]In 1859 his first painting was accepted and exhibited. His other paintings during that period were influenced by Camille Corot, who tutored him.[10] He and Corot both shared a love of rural scenes painted from nature. It was from Corot that Pissarro was inspired to paint outdoors, also called "plein air" painting. Pissarro found Corot, along with the work of Gustave Courbet, to be “statements of pictorial truth,” writes Rewald. He discussed their work often. Jean-François Millet was another whose work he admired, especially his “sentimental renditions of rural life”.[1]:12

Use of outdoor natural settings

Entrée du village de Voisins (1872)

- ”Work at the same time upon sky, water, branches, ground, keeping everything going on and equal basis and unceasingly rework until you have got it. Paint generously and unhesitatingly, for it is best not to lose the first impression.”[11]

With Monet, Cézanne, and Guillaumin

In 1859, while attending the free school, the Académie Suisse, Pissarro became friends with a number of younger artists who likewise chose to paint in the more realistic style. Among them were Claude Monet, Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cézanne. What they shared in common was their dissatisfaction with the dictates of the Salon. Cézanne’s work had been mocked at the time by the others in the school, and, writes Rewald, in his later years Cézanne "never forgot the sympathy and understanding with which Pissarro encouraged him."[1]:16 As a part of the group, Pissarro was comforted from knowing he was not alone, and that others similarly struggled with their art.

In 1869, Pissarro settled in Louveciennes and would often paint the road to Versailles in various seasons.[12] The Walters Art Museum.

In subsequent Salon exhibits of 1865 and 1866, Pissarro acknowledged his influences from Melbye and Corot, whom he listed as his masters in the catalog. But in the exhibition of 1868 he no longer credited other artists as an influence, in effect declaring his independence as a painter. This was noted at the time by art critic and author Émile Zola, who offered his opinion:

- ”Camille Pissarro is one of the three or four true painters of this day . . . I have rarely encountered a technique that is so sure.”[7]

Camille Pissarro and his wife, Julie Vellay, 1877, Pontoise

- ”The brightness of his palette envelops objects in atmosphere. . . He paints the smell of the earth.”[8]:35

In the late 1860s or early 1870s, Pissarro became fascinated with Japanese prints, which influenced his desire to experiment in new compositions. He described the art to his son Lucien:

- ”It is marvelous. This is what I see in the art of this astonishing people . . . nothing that leaps to the eye, a calm, a grandeur, an extraordinary unity, a rather subdued radiance. . . “[8]:19

Marriage and children

In 1871 he married his mother’s maid, Julie Vellay, a vineyard grower’s daughter, with whom he would later have seven children. They lived outside of Paris in Pontoise and later in Louveciennes, both of which places inspired many of his paintings including scenes of village life, along with rivers, woods, and people at work. He also kept in touch with the other artists of his earlier group, especially Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, and Frédéric Bazille.[7]The London years

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, having only Danish nationality and being unable to join the army, he moved his family to Norwood, then a village on the edge of London. However, his style of painting, which was a forerunner of what was later called “Impressionism,” did not do well. He writes to his friend, Theodore Duret, that “my painting doesn’t catch on, not at all...”[7]Pissarro met the Paris art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, in London, who became the dealer who helped sell his art for most of his life. Durand-Ruel put him in touch with Monet who was likewise in London during this period. They both viewed the work of British landscape artists John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, which confirmed to their belief that their style of open air painting gave the truest depiction of light and atmosphere, an effect that they felt could not be achieved in the studio alone. Pissarro’s paintings also began to take on a more spontaneous look, with loosely blended brushstrokes and areas of impasto, giving more depth to the work.[7]

- Paintings

Returning to France, in 1890 Pissarro again visited England and painted some ten scenes of central London. He came back again in 1892, painting in Kew Gardens and Kew Green, and also in 1897, when he produced several oils of Bedford Park, Chiswick.[15]

French Impressionism

Landscape at Pontoise, 1874

He soon reestablished his friendships with the other Impressionist artists of his earlier group, including Cézanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir, and Degas. Pissarro now expressed his opinion to the group that he wanted an alternative to the Salon so their group could display their own unique styles.

To assist in that endeavor, in 1873 he helped establish a separate collective, called the "Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs," which included fifteen artists. Pissarro created the group’s first charter and became the “pivotal” figure in establishing and holding the group together. One writer noted that with his prematurely gray beard, the forty-three year old Pissarro was regarded as a “wise elder and father figure” by the group.[7] Yet he was able to work alongside the other artists on equal terms due to his youthful temperament and creativity. Another writer said of him that “he has unchanging spiritual youth and the look of an ancestor who remained a young man”.[8]:36

Impressionist Exhibitions

The following year, in 1874, the group held their first 'Impressionist' Exhibition, which shocked and “horrified” the critics, who primarily appreciated only scenes portraying religious, historical, or mythological settings. They found fault with the Impressionist paintings on many grounds:[7]- The subject matter was considered “vulgar” and “commonplace,” with scenes of street people going about their everyday lives. Pissarro’s paintings, for instance, showed scenes of muddy, dirty, and unkempt settings;

- The manner of painting was too sketchy and looked incomplete, especially compared to the traditional styles of the period. The use of visible and expressive brushwork by all the artists was considered an insult to the craft of traditional artists, who often spent weeks on their work. Here, the paintings were often done in one sitting and the paints were applied wet-on-wet;

- The use of color by the Impressionists relied on new theories they developed, such as having shadows painted with the reflected light of surrounding, and often unseen, objects.

A "revolutionary" style

Pissarro showed five of his paintings, all landscapes, at the exhibit, and again Émile Zola praised his art and that of the others. One critic, the poet Armand Silvestre, credited Pissarro with being “basically the inventor of this [Impressionist] painting”. In the Impressionist exhibit of 1876 however, art critic Albert Wolf complained in his review, “Try to make M. Pissarro understand that trees are not violet, that sky is not the color of fresh butter . . .” Journalist and art critic Octave Mirbeau on the other hand, writes, “Camille Pissarro has been a revolutionary through the revitalized working methods with which he has endowed painting”.[8]:36According to Rewald, Pissarro had taken on an attitude more simple and natural than the other artists. He writes:

- “Rather than glorifying—consciously or not—the rugged existence of the peasants, he placed them without any ‘pose’ in their habitual surroundings, thus becoming an objective chronicler of one of the many facets of contemporary life.”[1]:20

Pissarro, Degas, and American impressionist Mary Cassatt self-published a journal of their original prints in the late 1870s, which contained a large group of their own fine etchings.[7] Art historian and the artist's great-grandson Joachim Pissarro notes that they “professed a passionate disdain for the Salons and refused to exhibit at them.”[6] Together they shared an “almost militant resolution” against the Salon, and through their later correspondences it is clear that their mutual admiration “was based on a kinship of ethical as well as aesthetic concerns”.[6]

Cassatt had befriended Degas and Pissarro years earlier when she joined Pissarro's newly formed French Impressionist group and gave up opportunities to exhibit in the United States. She and Pissarro were often treated as "two outsiders" by the Salon since neither were French or had become French citizens. However, she was "fired up with the cause" of promoting Impressionism and looked forward to exhibiting "out of solidarity with her new friends".[16] Toward the end of the Impressionist period, she began to avoid Degas, against whose "wicked tongue" she was unable to defend herself. Instead, she came to prefer the company of "the gentle Camille Pissarro", with whom she could speak frankly about the changing attitudes toward art.[17] She once described him as a teacher "that could have taught the stones to draw correctly."[7]

Neo-Impressionism period

By the 1880s, Pissarro began to explore new themes and methods of painting in order to break out of what he felt was an artistic “mire”. As a result, Pissarro went back to his earlier themes by painting the life of country people, which he had done in Venezuela in his youth. Degas described Pissarro’s subjects as “peasants working to make a living”.[7]However, this period also marked the end of the Impressionist period due to Pissarro’s leaving the movement. As Joachim Pissarro points out, “Once such a die-hard Impressionist as Pissarro had turned his back on Impressionism, it was apparent that Impressionism had no chance of surviving. . . “[8]:52

It was Pissarro’s intention during this period to help “educate the public” by painting people at work or at home in realistic settings, without idealizing their lives. Renoir, in 1882, referred to Pissarro’s work during this period as “revolutionary,” in his attempt to portray the "common man." Pissarro himself did not use his art to overtly preach any kind of political message, however, although his preference for painting humble subjects was intended to be seen and purchased by his upper class clientele. He also began painting with a more unified brushwork along with pure strokes of color.

Studying with Seurat and Signac

In 1884 he met Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, both of whom relied on a more “scientific” theory of painting by using very small patches of pure colors to create the illusion of blended colors and shading when viewed from a distance. Pissarro then spent the next four years, from 1885 to 1888, practicing this more time-consuming and laborious technique, referred to as pointillism. His work was distinctly different from his Impressionist works, and were on display in the 1886 Impressionist Exhibition, but under a separate section, along with works by Seurat, Signac, and his son Lucien.All four works were considered an “exception” to the eighth exhibition. Joachim Pissarro notes that virtually every reviewer who commented on Pissarro’s work noted “his extraordinary capacity to change his art, revise his position and take on new challenges.”[8]:52 One critic writes:

- ”It is difficult to speak of Camille Pissarro . . . What we have here is a fighter from way back, a master who continually grows and courageously adapts to new theories.”[8]:51

In 1884, art dealer Theo van Gogh asked Pissarro if he would take in his older brother, Vincent, as a boarder in his home. According to Pissarro’s son Lucien, his father was impressed by Van Gogh’s work and had “foreseen the power of this artist”, who was 23 years younger. Although Van Gogh never boarded with him, Pissarro did explain to him the various ways of finding and expressing light and color, ideas which he later used in his paintings, notes Lucien.[1]:43

Abandoning Neo-Impressionism

Pissarro eventually turned away from Neo-Impressionism, claiming its system was too artificial. He explains in a letter to a friend:- ”Having tried this theory for four years and having then abandoned it . . . I can no longer consider myself one of the neo-impressionists. . . It was impossible to be true to my sensations and consequently to render life and movement, impossible to be faithful to the effects, so random and so admirable, of nature, impossible to give an individual character to my drawing, [that] I had to give up.”[1]:41

But the change also added to Pissarro’s continual financial hardship which he felt until his 60s. His “headstrong courage and a tenacity to undertake and sustain the career of an artist”, writes Joachim Pissarro, was due to his “lack of fear of the immediate repercussions” of his stylistic decisions. In addition, his work was strong enough to “bolster his morale and keep him going”, he writes.[6] His Impressionist contemporaries, however, continued to view his independence as a “mark of integrity”, and they turned to him for advice, referring to him as “Père Pissarro” (father Pissarro).[6]

Later years

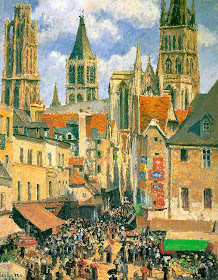

In his older age Pissarro suffered from a recurring eye infection that prevented him from working outdoors except in warm weather. As a result of this disability, he began painting outdoor scenes while sitting by the window of hotel rooms. He often chose hotel rooms on upper levels to get a broader view. He moved around northern France and painted from hotels in Rouen, Paris, Le Havre and Dieppe. On his visits to London, he would do the same.[7]Pissarro died in Paris on 13 November 1903 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.[3]

Legacy and influence

During the period Pissarro exhibited his works, art critic Armand Silvestre had called Pissarro the "most real and most naive member" of the Impressionist group.[18] His work has also been described by art historian Diane Kelder as expressing "the same quiet dignity, sincerity, and durability that distinguished his person." She adds that "no member of the group did more to mediate the internecine disputes that threatened at times to break it apart, and no one was a more diligent proselytizer of the new painting."[18]According to Pissarro’s son, Lucien, his father painted regularly with Cézanne beginning in 1872. He recalls that Cézanne walked a few miles to join Pissarro at various settings in Pontoise. While they shared ideas during their work, the younger Cézanne wanted to study the countryside through Pissarro’s eyes, as he admired Pissarro’s landscapes from the 1860s. Cézanne, although only nine years younger than Pissarro, said that “he was a father for me. A man to consult and a little like the good Lord.”[7]

Lucien Pissarro was taught painting by his father, and described him as a “splendid teacher, never imposing his personality on his pupil.” Gauguin, who also studied under him, referred to Pissarro “as a force with which future artists would have to reckon”.[8] Art historian Diane Kelder notes that it was Pissarro who introduced Gauguin, who was then a young stockbroker studying to become an artist, to Degas and Cézanne.[18] Gauguin, near the end of his career, wrote a letter to a friend in 1902, shortly before Pissarro’s death:

- ”If we observe the totality of Pissarro’s work, we find there, despite fluctuations, not only an extreme artistic will, never belied, but also an essentially intuitive, purebred art . . . He was one of my masters and I do not deny him.”[1]:45

Lost and found paintings

During the early 1930s throughout Europe, Jewish owners of numerous fine art masterpieces found themselves forced to give up or sell off their collections for minimal prices due to anti-Jewish laws created by the new Nazi regime. Many Jews were forced to flee Germany. When those forced into exile owned valuables, including artwork, they were often seized by officials who either kept them as personal possessions or sold them at auction for cash. In the decades after World War II, many art masterpieces were found on display in various galleries and museums in Europe and the United States. Some, as a result of legal action, were later returned to the families of the original owners. Many of the recovered paintings were then donated to the same or other museums as a gift.[19]One such lost piece, Pissarro's 1897 oil painting, "Rue St. Honoré, Apres Midi, Effet de Pluie," was discovered hanging at Madrid's government-owned museum, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. However, in January 2011, the Spanish government denied a request by the U.S. ambassador to return the painting to the Cassirer family in California, which claims with proof that it was among those illegally taken by Nazis in Germany.[20] The case is scheduled for trial by the U.S. District Ct. in Los Angeles July 3, 2012.[21]

In other legal cases, Pissarro's "Le Quai Malaquais, Printemps," is said to have been similarly stolen, along with the estimated 650,000 lost works of art, including those by other French Impressionists.[22] In 1999, Pissarro's "Boulevard Montmartre, Spring, 1887" turned up in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem after being donated, its donor having been unaware of its pre-war provenance.[23]

In January 2012, a work stolen 30 years earlier from a French museum was returned. The piece, "Le Marché aux Poissons" ("The Fish Market" in English), is a color monotype, a one-of-a-kind print made by painting on glass and then transferring the wet paint to a piece of paper.[24]

During his lifetime, Camille Pissarro sold few of his paintings. By the recent turn of the century, however, his paintings were selling for millions. The highest auction record for the artist was set on November 6, 2007 at Christie's in New York, where a group of four paintings, "Les Quatre Saisons" (the Four Seasons) sold for $14,601,000 (estimate $12,000,000 - $18,000,000). The auction record for a single painting by the artist is $7,026,500, set at Sotheby's in New York on November 4, 2009, for Pissarro's "Le Pont Boieldieu et la gare d'Orléans, Roeun, Soleil."

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment